Foreign Note

- Jun 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Yasir Masud The author talks about his act of defiance in front of an audience after being bullied as a ‘Paki’ at school in England. There is a silence beneath grey skies that feels different when it’s aimed at you. Not indifference, not quite, but a sort of accusation without words. Manchester, 1993. The year I became foreign not just in body, but in spirit. I was twelve.

We had come from Islamabad—not fleeing war, not seeking asylum, not even chasing fortune. My mother, a civil servant back home, had secured a scholarship for postgraduate study. A year abroad, she said. A chance to grow. She brought me with her, her only child. My father remained behind, married to his work and silence.

I had been raised gently, cocooned by air-conditioned cars and soft-voiced housemaids, by books in English and fruit from baskets. But Manchester was cold in a way that had nothing to do with temperature. The council estate where we lived was chipped and sullen, its walls stained with the quiet exhaustion of the working class. There were no servants here. No mangoes. No deference. Just suspicion, grey brick, and the faint scent of mildew rising from the carpets.

I was enrolled in the local comprehensive, where the playground was a battlefield and accents were currency. Mine was clipped, too formal. I said ‘perhaps’ and “excuse me.” They said ‘innit’ and ‘f*** off.’ I was a mismatch in every way.

They called me ‘Paki.’

With ease. With pleasure.

The word struck not like a whip, but like a cough—habitual, effortless.

Once, a man in a car rolled down his window and spat at me. I hadn’t even looked at him. Just crossing the road with my schoolbag swinging and my eyes lowered, as I’d been taught. But I existed, and that was enough.

In school, teachers mispronounced my name and never corrected the boys who mocked it. One said it sounded like a disease. Another told me I was “too sensitive” when I flinched.

I began to shrink inside my own body. Walked more softly. Laughed less. Ate my lunch alone, behind the boiler room, where the radiator hissed like it knew shame too.

That was the day I learned how closely humiliation can live beside hope. How offering the truest part of yourself can become an invitation to wound.

At home, my mother grew smaller too. Her hands, once always busy—correcting papers, slicing apples, smoothing my hair—began to tremble. She wore scarves indoors, even when the heating worked. She said it was just the flu. Then just a ‘procedure’. Later, I learned the word. Cancer. A hard consonant, lodged like a stone.

One night, I heard her crying through the wall. I remember being angry at the sound. Not because she was crying, but because I couldn’t fix it. Because her pain was private and I was twelve and useless.

When I asked if I would ever have a brother or sister, she turned her face to the window.

That silence—it had weight. It pressed into my chest and made a home there.

I never asked again.

I found the music by accident. A noticeboard at the community centre advertised free classes: ‘Asian Arts for Youth.’ I didn’t go for identity. I went because it was warm and I had nowhere else.

They gave me a cushion and a drone; the low hum of a tanpura, like breath held too long. The instructor wore silver bangles and always looked vaguely disappointed, but when I sang my first scale, he blinked slowly and said, “Again.”

So I sang again. And again. Until the notes stopped breaking, and began to bend.

Raag Yaman. Raag Bhairavi. Raag Malkauns. Each one like a prayer in a language older than punishment.

It was the only place I felt seen.

And so, like a fool, I brought it to school.

Culture Day.

I stood on stage in my pressed shirt and sang a bandish—slow, deliberate, rich with longing. The drone played. My voice, clear but trembling, stretched across the assembly hall. I held every note like it might carry me away.

They laughed.

The headmaster smiled through it. A teacher mouthed “very nice.” A boy in the back made a bleating noise, said I sounded like a goat giving birth.

I finished the song anyway.

That was the day I learned how closely humiliation can live beside hope. How offering the truest part of yourself can become an invitation to wound. I knew they wouldn’t understand the music. I just didn’t expect them to despise it.

But here’s the thing: I didn’t stop singing.

I just stopped expecting anyone to listen.

I sang in stairwells, in empty launderettes, into the folds of my pillow. The music became a room I could enter and lock behind me.

But it was also a mirror.

And what it showed me wasn’t always beautiful.

I began to suspect that even my talent was foreign. That no matter how well I sang, it would always mark me as different. And maybe—just maybe—I leaned into that difference too hard. Turned my voice into a weapon. A spotlight. A dare.

You want to laugh?

Here. I’ll give you something worth laughing at.

Let me hand you my heart in ragas.

Break it properly this time.

There is a kind of power in self-sabotage. A dark, clever power. I learned it young.

It’s taken me years to realise I mistook survival for expression. That singing didn’t protect me. It just preserved me, like something fossilized—intact but unreachable.

Sometimes, I wonder what I would have become if they hadn’t laughed. If someone had clapped. If someone had said, “Yes, that’s beautiful. Keep going.”

But no one did.

So I kept going anyway.

Alone.

And in a way, I suppose, that’s what music is: a note held out for someone who may never answer.

Yasir Masud grew up crisscrossing between the UK, USA, and Pakistan, collecting languages, identities, and a healthy dose of cultural confusion. A polyglot by circumstance, a classically trained vocalist by obsession, a lawyer by profession and a writer by midlife necessity, he now lives in Pakistan with his spouse and three gloriously independent teens. His work navigates the absurdities of a multicultural life with satire, survival, and the occasional melody—stumbling into this latest act with equal parts soul and sincerity.

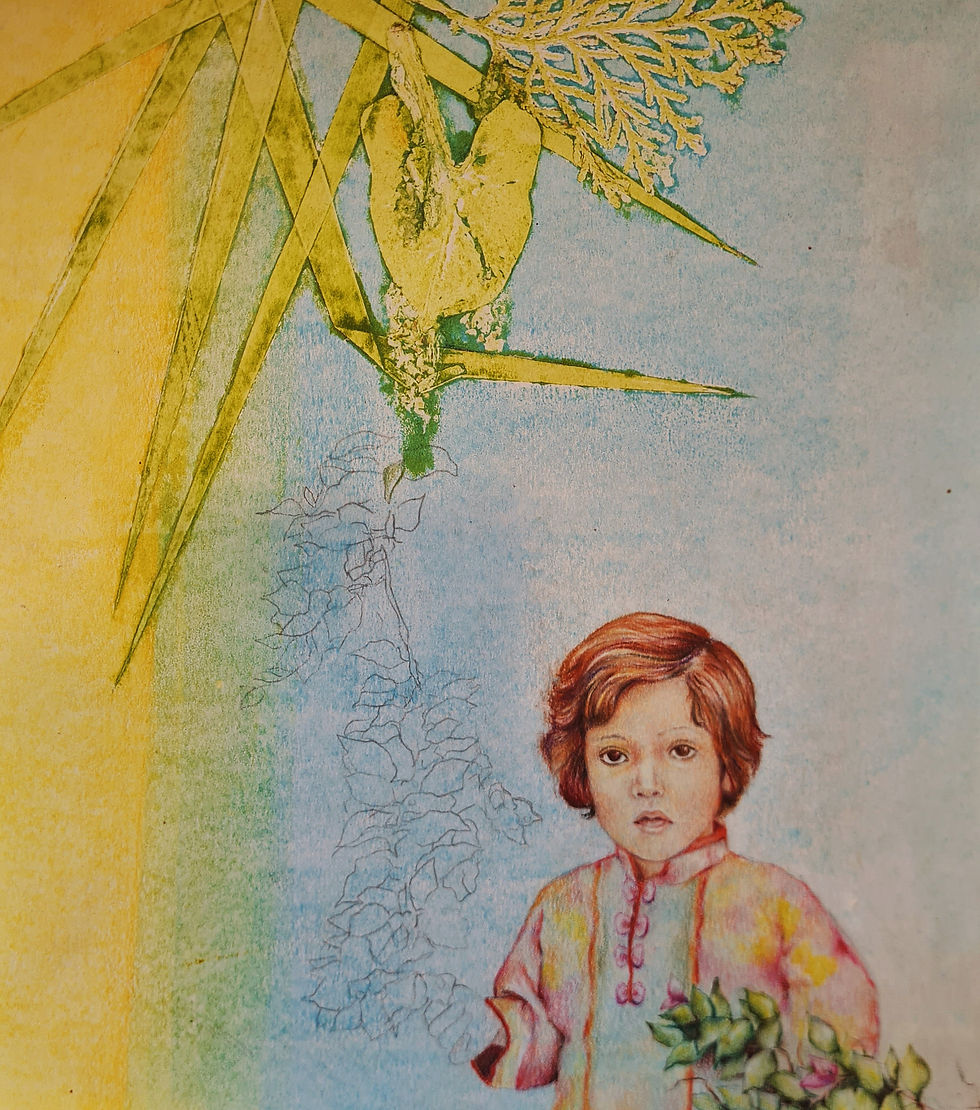

Fajr Falak is a Lahore based visual artist. With a BFA in miniature painting, Falak has recently graduated in Fine Arts from National College of Arts, Lahore, in 2024. The main subject of Fajr’s work revolves around remembrance through discussion and observational studies. Falak creates artworks using a range of mediums and her art-making process consists of rigorous observation, documentation, painting in detail and combining her work with written poetry. Even though miniature painting is her major, Falak adds newer mediums to her work and experiments with backgrounds to challenge the existing boundaries and implications of miniature painting.

From the show 'Fractured and Fluid', at Kaleido Kontemporary.

"This is one of the most powerful and heartbreaking pieces I’ve read in a long time. The raw honesty, the quiet strength, and the pain woven into every line truly touched me. Your voice speaks for so many who have suffered in silence, not just from racism, but from the deep loneliness of being unseen. Thank you for sharing your story with such courage and grace. This isn’t just a personal memory, it’s a reflection of a much larger truth."